The Russian Empire as a Lesson for Walking

I think about the Russian Army quite a lot.

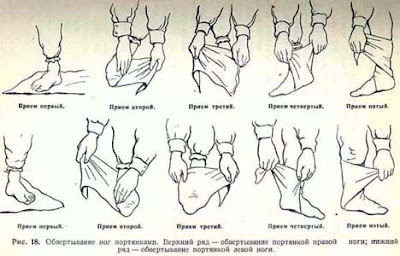

Up until 2013, they weren't issued socks with military dress. From Peter Alexeyevich's Battle of Systerbäck in 1703 to the Russian Army's march into Georgia, Russian soldiers have worn portyanki, a footwrap made from squares of cloth in the summer and flannel in the winter. Elaborate methods of wrapping the foot meant that portyanki could often offer more in the way of ameliorating sore, blistered feet than fitted socks ever could. Soldiers could also stuff excess material from the wrap into spaces in standard issue boots that prevented the constant reopening of blisters, or to fill out the boot if their feet didn't quite do the job.

It is easy, perhaps even somewhat romantic, to think of the Russian soldier mastering the tundras of Siberia, or the rugged and mountainous Caucasian region, or even the first Russian troops landing on the sparsely-populated Sakhalin Island to Russia's farthest east. Their feet wrapped, boots stuffed, their ability to manipulate themselves around their surroundings enhanced; a decisive factor in how Russia became Russia has to be the portyanki. It allows for the corporeal Russian body, prone to infection and disease and septicemia, to truly master its physical empire. The exigent obstacles of the harshest climates of Eurasia bend to the might of such a simple invention.

I think by this point it is reasonable to say that I do not have the constitution to be a Russian soldier. I cannot imagine myself chasing Napoleon's Grand Armee out of Borodino and back into Europe. I once had a total physical meltdown, essentially, because I slept in a tent at a festival. It rained harshly, and as the drops slammed into the canvas cover of the secluded space in which *insert anonymous band here* were playing, as my ears were assaulted by the maelstrom of music, rain, and people muttering and shouting, glass breaking, cups crunching, wind howling; I broke down into floods of tears.

Many autistic people would know that a festival is something to be avoided. It was a steep learning curve for me. I didn't have my diagnosis at this point, and part of the pretence of 'masking' (pretending that my triggers don't exist) is doing things you’re uncomfortable with for people you love for fear of ostracisation. My stunningly understanding girlfriend, who I am blessed to still be with, took me back to our tent and held me as I wept and longed for home, a place that would soothe my jarred and assaulted body. This condition is as much a reality for her as it is for me. Breaking down into uncontrollable tears is a common theme running through this project. It is the main way in which my physical breakdowns manifest. It can be really devastating, but I can also appreciate that it can be quite funny. When my sister got a new boyfriend, we went through a stage of going regularly for family meals. I would find myself tormented by the loud, dimly-lit environment, kids screeching, balloons rubbing and swaying, the balance of the place just totally off-kilter. I'd tear up out of nowhere and the poor man must have initially thought I'd found his presence extremely traumatising. This condition can provide moments of hopeless loneliness. Though in his case, it can bring out the best in those around you. Hence, I think its fair to suggest that autistic people unanimously long for their own metaphorical portyanki, whatever form that may take.

Which finally brings me to the useful part of this post. That is, unless you want to stun your friends with staggeringly average-tier trivia about Russian footwear. As something that enables the environment, atmosphere, smells, feels and sounds around you to be manipulated for the better, portyanki stands as a symbol for something autistic people reach to every time we access the outside world. Something that makes it easier, something that eases the genuine torment.

For, in public health discourse, walking is the best antidote for a wide and diverse range of health conditions. It is something that I idealise personally, as an autistic person. One foot in front of the other. No systemic obstacles, no socio-economic barriers or accompanying mental anguish. Or so I naively always assume.

I step out in my tight-fitting footwear, for what is being autistic if not conforming to some stereotypes? An older girl once laughed at me in school for wearing DC trainers with huge, looping laces hanging off the vamp of the shoe. Looking back, it was fashionable for laces to have gone unseen. But I didn’t get it. I cried. But I knew I had to maintain this sense of self I had built through tightly-fitting shoes. I couldn’t, and still can’t, explain it. Such is autism.

Back to the present. I head down my road. The noise of cars brings my mind to the poem The Wish by Abraham Cowley. He describes certain stimuli present in cities as "stings". Cars definitely sting. They sting audibly but they hit something much deeper. I feel it more basely. I am nudged into the inner pavement, recoiling from the traffic, head down and earphones in. A desperate measure against the stinging. Oftentimes I listen to nothing. The earphones just rest there, a groyne against the raging sea. The stings still send my mind whirling. It can be anything. Pokemon. Albert Camus. Fernandinho's name. It doesn't matter. The stings come and they're relentless.

Books can act as such a good reference point for the way autistic people experience the world. Small children latch onto fantasy characters as a method of rejecting neurotypical standards of emotional exchange. I do something similar, but with poetry and literature. As my autistic mind whirs, it warns me against doing this in fear that people will reject me as pretentious and morbid. But anything to ease the stings.

As with tattooing, after 10 minutes or so my body starts to acclimatise. One foot in front of the other. Portyanki. My feet feel firm on the ground, I feel rooted against the urban background in which I walk.

But somebody is coming the other way. As we pass, some form of social ritual ensues. A small glance perhaps, or a nod. A simple, cursory movement to the side, to distance ourselves further. During social distancing, this is a *very* good idea. But I don't usually understand. There's no usual medical or practical value. Or even social, I suppose. I appreciate rituals exist, and having autism affirms that fact. But this form of exchange feels like there's something people know that I don't. Did the Freemasons induct everybody into the world with Pavlovian conditioning, things = necessary, other things = not necessary, and did I miss my induction?

If I did, the next phase of this dance is outright distressing. Another person approaches. But somebody appears to have started walking behind me. I quickly align myself to their path, gauging whether or not they're: a) walking faster, b) using this newly-created draft to gain some ground or c) walking unpredictably. How do I move to accomodate both people? How do I sense what the right thing is to do? Are we all on a continental bearing and, given that the two people out of my control bump into one another, am I on course for a very real kind of social death? I feel reality slipping and a photocopy slide into its place, a sheet of paper with uncodified rules which only I am reading from. I'm mentally paralysed but my body carries on walking. It has a sense of abandon that my mind could only dream of. The poem Danse Russe by William Carlos Williams jumps to the front of my mind. A man, with naked and reckless abandon, dances at sunrise before he resumes his duties as a father and landlord. A beautiful Russian dance. Why can these people, who are inadvertently distressing me so, just stop in their tracks and appreciate the cumulative beauty that words on a page can have?

Obviously they can't. They have places to be. They have jobs to work, just like myself. Its not their fault, but I feel a deep ball of fire burn within me. Sometimes literally, if the stings reappear. They navigate the pavements with such ease. For me, walking down the road often turns into an existential test. Autistic children probably, almost certainly, feel the same. They have their imaginations, learned behaviours and fantasies to ease themselves but, equipped with lesser standards of acuity, I imagine they have feelings they simply can't express. They have to meltdown. There's no other choice. Portyanki can't be accessed for either one of us.

Obviously, I get to where I want to go. The processes I have described happen almost exclusively internally. They exhaust me. I feel mentally drained before a day of study or work has begun and most people, understandably, don't get it. Morning strolls through Manchester to campus can be so purifying for my colleagues and other students. I get it. But I find myself deodorising over my intense walking experiences.

I can deflect the stings altogether, eventually. Though where I end up is at the mercy of my impulsive body. My mind oscilates violently between 'one foot in front of the other' and 'what form of cultural exchange falls under nationalism?' Or more important questions of the sort. Half the time I find myself in happy spaces. Reddish Vale is stunningly beautiful. So much so, the ATVs ridden somewhere in a nearby field often don't sting. To find yourself at a sublime location eases the terror. You feel fine that you don't matter. Or at least the universe is indifferent. Half the time, I find myself stinging. I end up either rambling aimlessly or find myself in intensely reflective situations or places.

My grandad's grave was one such place, very recently. He was my best friend and he died when I was ten. I still grieve for him. I don't visit him often. But I don't know how to process my loss. It all adds up.

Portyanki is something we can't reach, even if we try our hardest. But both sides of the spectrum need to be okay with that. Especially us. We drive ourselves insane wondering why we're so different and why we can't process the most simple of social rules. But that's okay. We have each other and, eventually, with patience, the understanding and love of those around us.

---

Abraham Cowley, The Wish, https://englishverse.com/poems/the_wish.

William Carlos Williams, Danse Russe, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46483/danse-russe.

Up until 2013, they weren't issued socks with military dress. From Peter Alexeyevich's Battle of Systerbäck in 1703 to the Russian Army's march into Georgia, Russian soldiers have worn portyanki, a footwrap made from squares of cloth in the summer and flannel in the winter. Elaborate methods of wrapping the foot meant that portyanki could often offer more in the way of ameliorating sore, blistered feet than fitted socks ever could. Soldiers could also stuff excess material from the wrap into spaces in standard issue boots that prevented the constant reopening of blisters, or to fill out the boot if their feet didn't quite do the job.

It is easy, perhaps even somewhat romantic, to think of the Russian soldier mastering the tundras of Siberia, or the rugged and mountainous Caucasian region, or even the first Russian troops landing on the sparsely-populated Sakhalin Island to Russia's farthest east. Their feet wrapped, boots stuffed, their ability to manipulate themselves around their surroundings enhanced; a decisive factor in how Russia became Russia has to be the portyanki. It allows for the corporeal Russian body, prone to infection and disease and septicemia, to truly master its physical empire. The exigent obstacles of the harshest climates of Eurasia bend to the might of such a simple invention.

I think by this point it is reasonable to say that I do not have the constitution to be a Russian soldier. I cannot imagine myself chasing Napoleon's Grand Armee out of Borodino and back into Europe. I once had a total physical meltdown, essentially, because I slept in a tent at a festival. It rained harshly, and as the drops slammed into the canvas cover of the secluded space in which *insert anonymous band here* were playing, as my ears were assaulted by the maelstrom of music, rain, and people muttering and shouting, glass breaking, cups crunching, wind howling; I broke down into floods of tears.

Many autistic people would know that a festival is something to be avoided. It was a steep learning curve for me. I didn't have my diagnosis at this point, and part of the pretence of 'masking' (pretending that my triggers don't exist) is doing things you’re uncomfortable with for people you love for fear of ostracisation. My stunningly understanding girlfriend, who I am blessed to still be with, took me back to our tent and held me as I wept and longed for home, a place that would soothe my jarred and assaulted body. This condition is as much a reality for her as it is for me. Breaking down into uncontrollable tears is a common theme running through this project. It is the main way in which my physical breakdowns manifest. It can be really devastating, but I can also appreciate that it can be quite funny. When my sister got a new boyfriend, we went through a stage of going regularly for family meals. I would find myself tormented by the loud, dimly-lit environment, kids screeching, balloons rubbing and swaying, the balance of the place just totally off-kilter. I'd tear up out of nowhere and the poor man must have initially thought I'd found his presence extremely traumatising. This condition can provide moments of hopeless loneliness. Though in his case, it can bring out the best in those around you. Hence, I think its fair to suggest that autistic people unanimously long for their own metaphorical portyanki, whatever form that may take.

Which finally brings me to the useful part of this post. That is, unless you want to stun your friends with staggeringly average-tier trivia about Russian footwear. As something that enables the environment, atmosphere, smells, feels and sounds around you to be manipulated for the better, portyanki stands as a symbol for something autistic people reach to every time we access the outside world. Something that makes it easier, something that eases the genuine torment.

For, in public health discourse, walking is the best antidote for a wide and diverse range of health conditions. It is something that I idealise personally, as an autistic person. One foot in front of the other. No systemic obstacles, no socio-economic barriers or accompanying mental anguish. Or so I naively always assume.

I step out in my tight-fitting footwear, for what is being autistic if not conforming to some stereotypes? An older girl once laughed at me in school for wearing DC trainers with huge, looping laces hanging off the vamp of the shoe. Looking back, it was fashionable for laces to have gone unseen. But I didn’t get it. I cried. But I knew I had to maintain this sense of self I had built through tightly-fitting shoes. I couldn’t, and still can’t, explain it. Such is autism.

Back to the present. I head down my road. The noise of cars brings my mind to the poem The Wish by Abraham Cowley. He describes certain stimuli present in cities as "stings". Cars definitely sting. They sting audibly but they hit something much deeper. I feel it more basely. I am nudged into the inner pavement, recoiling from the traffic, head down and earphones in. A desperate measure against the stinging. Oftentimes I listen to nothing. The earphones just rest there, a groyne against the raging sea. The stings still send my mind whirling. It can be anything. Pokemon. Albert Camus. Fernandinho's name. It doesn't matter. The stings come and they're relentless.

Books can act as such a good reference point for the way autistic people experience the world. Small children latch onto fantasy characters as a method of rejecting neurotypical standards of emotional exchange. I do something similar, but with poetry and literature. As my autistic mind whirs, it warns me against doing this in fear that people will reject me as pretentious and morbid. But anything to ease the stings.

As with tattooing, after 10 minutes or so my body starts to acclimatise. One foot in front of the other. Portyanki. My feet feel firm on the ground, I feel rooted against the urban background in which I walk.

But somebody is coming the other way. As we pass, some form of social ritual ensues. A small glance perhaps, or a nod. A simple, cursory movement to the side, to distance ourselves further. During social distancing, this is a *very* good idea. But I don't usually understand. There's no usual medical or practical value. Or even social, I suppose. I appreciate rituals exist, and having autism affirms that fact. But this form of exchange feels like there's something people know that I don't. Did the Freemasons induct everybody into the world with Pavlovian conditioning, things = necessary, other things = not necessary, and did I miss my induction?

If I did, the next phase of this dance is outright distressing. Another person approaches. But somebody appears to have started walking behind me. I quickly align myself to their path, gauging whether or not they're: a) walking faster, b) using this newly-created draft to gain some ground or c) walking unpredictably. How do I move to accomodate both people? How do I sense what the right thing is to do? Are we all on a continental bearing and, given that the two people out of my control bump into one another, am I on course for a very real kind of social death? I feel reality slipping and a photocopy slide into its place, a sheet of paper with uncodified rules which only I am reading from. I'm mentally paralysed but my body carries on walking. It has a sense of abandon that my mind could only dream of. The poem Danse Russe by William Carlos Williams jumps to the front of my mind. A man, with naked and reckless abandon, dances at sunrise before he resumes his duties as a father and landlord. A beautiful Russian dance. Why can these people, who are inadvertently distressing me so, just stop in their tracks and appreciate the cumulative beauty that words on a page can have?

Obviously they can't. They have places to be. They have jobs to work, just like myself. Its not their fault, but I feel a deep ball of fire burn within me. Sometimes literally, if the stings reappear. They navigate the pavements with such ease. For me, walking down the road often turns into an existential test. Autistic children probably, almost certainly, feel the same. They have their imaginations, learned behaviours and fantasies to ease themselves but, equipped with lesser standards of acuity, I imagine they have feelings they simply can't express. They have to meltdown. There's no other choice. Portyanki can't be accessed for either one of us.

Obviously, I get to where I want to go. The processes I have described happen almost exclusively internally. They exhaust me. I feel mentally drained before a day of study or work has begun and most people, understandably, don't get it. Morning strolls through Manchester to campus can be so purifying for my colleagues and other students. I get it. But I find myself deodorising over my intense walking experiences.

I can deflect the stings altogether, eventually. Though where I end up is at the mercy of my impulsive body. My mind oscilates violently between 'one foot in front of the other' and 'what form of cultural exchange falls under nationalism?' Or more important questions of the sort. Half the time I find myself in happy spaces. Reddish Vale is stunningly beautiful. So much so, the ATVs ridden somewhere in a nearby field often don't sting. To find yourself at a sublime location eases the terror. You feel fine that you don't matter. Or at least the universe is indifferent. Half the time, I find myself stinging. I end up either rambling aimlessly or find myself in intensely reflective situations or places.

My grandad's grave was one such place, very recently. He was my best friend and he died when I was ten. I still grieve for him. I don't visit him often. But I don't know how to process my loss. It all adds up.

Portyanki is something we can't reach, even if we try our hardest. But both sides of the spectrum need to be okay with that. Especially us. We drive ourselves insane wondering why we're so different and why we can't process the most simple of social rules. But that's okay. We have each other and, eventually, with patience, the understanding and love of those around us.

---

Abraham Cowley, The Wish, https://englishverse.com/poems/the_wish.

William Carlos Williams, Danse Russe, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46483/danse-russe.

Comments

Post a Comment